We had just set the Christmas tree in the flimsy, three-legged, red-and-green metal stand, and tightened the three bolts to hold it. This was Christmas of ’69 or ’70. I was still living at home, and was on break from college. I was at my friend Lee’s house, helping him put up the family Christmas tree in the living room. It was a real tree, about 8 feet tall.

We stood back to see how the tree looked. It started to lean slowly, then faster. Before we could stop it the Christmas tree crashed onto the butsudon. Hearing the noise, Okaasan sprang from the kitchen into the living room, yelling in Japanese.

I grew up in northeast Kansas City or, simply, Northeast, as opposed to, say, Prairie Village or Independence. Northeast was a place that, as some describe it, had two kinds of people: Italians and white people.

I lived on Belmont, across the street from Monkey Wards, the giant department store and mail-order house that competed with Sears, which was over at Truman Road and Cleveland.

Lee’s family, the Watermans, lived in one of the saltbox houses along the short block of Gladstone Boulevard that was right across the street from Indian Mound (which may or may not be a real Indian Mound but us kids thought so). Lee’s dad, Homer, had been in the U.S. Army of Occupation in Tokyo, Japan, in 1945. There he met Miyoko Isohara, whom he married and, in the early 1950s, returned to his home in Eldridge, Missouri, near Lebanon, with Miyoko and their two young sons, Alan, and Lee, four years younger. (Lee was my age.)

Eventually they moved to Kansas City where Homer worked as a TV repairman. Best I could tell, they were the only Japanese in Northeast. From them, I learned about nori, miso soup and tempura shrimp; from me, Lee and Alan learned about meatballs, mostaccioli and olive salad.

When I was around thirteen, Homer moved out, down to Springfield, leaving Miyoko a single mom with two boys. (Everyone but us kids called her Miki. Alan and Lee called her “Okaasan” – mom in Japanese; I called her Mrs. Waterman.)

Miki’s English was heavily accented, but she managed to get waitressing jobs. Eventually she landed a steady gig at the Oriental Inn, a Chinese restaurant owned by Emi, another Japanese war bride, who lived in Raytown. (The food was great.)

The Christmas tree had struck a glancing blow on the butsudon and knocked over a water cup and a few stacks of coins, offered from Miki’s waitressing tips. A butsudon is a Buddhist altar. As home altars go, this was fancy, maybe two and a half feet wide, five feet tall, with lights inside. Miki had it fixed up nice in a corner of the living room. Twice a day, morning and evening, she prayed – chanted – before that altar.

Before Lee and I could pick up the mess, Miki, angrily speaking Japanese, had opened the front door, seized the top of the tree, and dragged it partly outside. Lee yelled, also in Japanese, for her to stop.

Immediately we grabbed the other end – the trunk – of the tree, Lee and Okaasan still arguing in Japanese . My elementary Japanglish couldn’t keep up with them.

“What’s she saying?” I asked Lee.

“She’s gonna drag the tree outside and burn it.”

There we were: Two 19-year-old guys and a 40-something, 5-foot-something, furious Japanese woman having a tug of war over a Christmas tree. Okaasan was hell-bent on setting fire to the tree on the front lawn. And she was winning.

We were both yelling, “No! Stop!” Okaasan was speaking fast in Japanese with Lee simultaneously giving me a running translation while talking back to her in Japanese – “Okaasan! Iye!” “No!”

This wasn’t working. Then Lee tried another approach, in English.

“Okaasan, stop! The tree didn’t mean any harm! It’s a good tree! If you burn it, we’ll just have to go buy another one!” I chimed in likewise. “Yes! It’s a nice tree! It didn’t mean to hit your butsudon! We’ll fix it!”

By now, Okaasan was on the front porch, with the tree almost out the door. Cold air flooded the living room. We kept up our back forth in English (me) and Japanese (Lee and Miki). Somehow, Lee got through. Okaasan finally saw the hilarious absurdity of it all and started laughing. Then Lee and I started laughing. We all relaxed and just sat down where we were, on the floor, on the porch. The tree was safe.

In much better spirits, we pulled the Christmas tree back inside, set it back up, and this time made sure it was stable. Then we helped Okaasan neatly stack the coins as they were, in their rightful place.

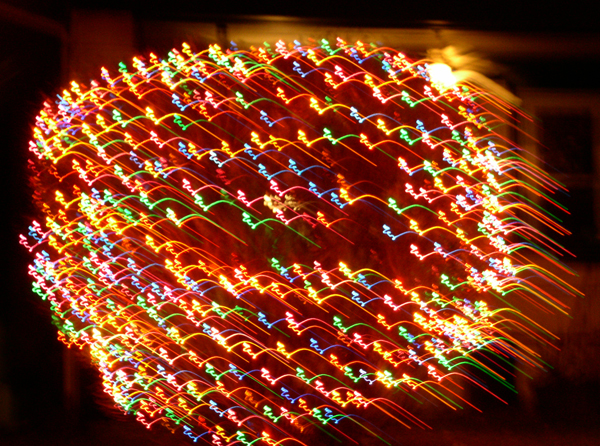

We picked up where we left off, finished hanging bulbs and stringing lights on the tree. Lee plugged in the lights. That glowing Christmas tree light filled the room and warmed up the winter night.

Okaasan was pleased with the results. “Ah, pretty, ne?”

“Honto!” we agreed. “Yeah!”

Photo © Frank C. Siraguso